Kabylia and the Historical Rejection of Centralized Islamic Authority

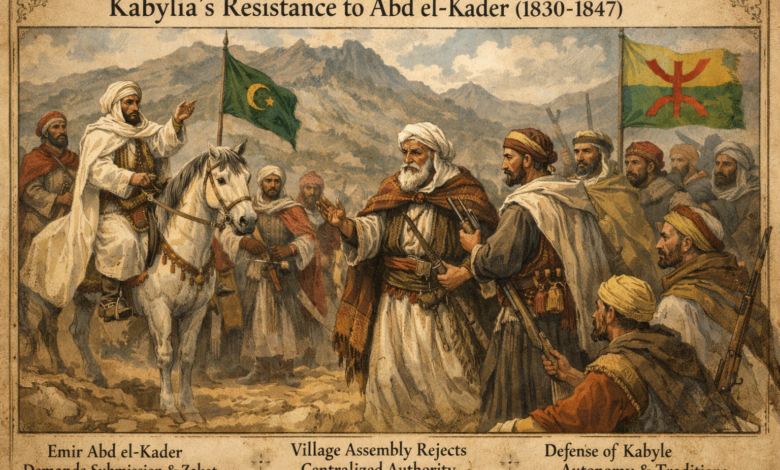

Resistance to Emir Abd el-Kader (1830–1847

Kabylia, the mountainous region of northern Algeria inhabited by the Kabyle Amazigh population, has long been characterized by strong traditions of local autonomy and resistance to centralized authority. Due to its rugged geography and deeply rooted communal institutions, Kabylia historically remained only marginally integrated into the political structures that governed surrounding lowland regions.

Autonomy before the French conquest

During the Ottoman period (sixteenth to early nineteenth centuries), the Regency of Algiers exercised at most a nominal influence over Kabylia. Ottoman authority relied primarily on negotiated arrangements rather than direct administration. Many Kabyle communities paid symbolic tribute or maintained diplomatic relations with Ottoman officials, but they consistently rejected permanent garrisons, taxation, or centralized governance.

Kabyle society was organized around village-based assemblies (tajmaât), which regulated political, judicial, and social affairs through collective deliberation. Customary law (qanun) prevailed over religious or imperial legislation, reinforcing a decentralized system in which authority derived from communal consensus rather than vertical power structures. This autonomy was not merely geographic but institutional and cultural.

Abd el-Kader’s project of Islamic centralization

The tension between Kabylia and centralized authority became particularly evident during the rise of Abd el-Kader (1808–1883). Proclaimed emir in 1832, Abd el-Kader sought to organize resistance against French conquest by establishing a centralized Islamic polity grounded in jihad and religious legitimacy. His project aimed to unify diverse Algerian regions under a structured emirate, combining military mobilization, fiscal authority, and religious governance.

Between 1838 and 1839, Abd el-Kader attempted to extend his authority into Kabylia. He demanded allegiance from tribal leaders, the payment of zakat (religious tax), and the integration of Kabyle fighters into his military structure. To enforce his rule, he appointed khalifas (deputies), notably Ben Salem, tasked with administering Kabyle territories between 1839 and 1843.

Kabyle refusal and resistance

Despite Abd el-Kader’s religious credentials as both a marabout and a sharif (a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad), Kabyle communities overwhelmingly rejected submission. French military observers Eugène Daumas and Paul Fabar noted in La Grande Kabylie: Études historiques (1847) that the emir “was unable to win Kabylia through persuasion,” despite sustained efforts.

Several factors underpinned this resistance. Kabyle leaders viewed Abd el-Kader’s centralized Islamic state as incompatible with their decentralized political culture. The emir’s reliance on appointed deputies clashed with the authority of village assemblies, while the imposition of religious taxation was perceived as an infringement on communal autonomy. Tribal rivalries and longstanding suspicion toward external authority—whether Ottoman, Arab, or colonial—further undermined Abd el-Kader’s influence.

Kabyle distrust was reinforced by Abd el-Kader’s diplomatic dealings with the French, including negotiated truces that some Kabyle leaders interpreted as evidence of political opportunism. Raids and coercive measures undertaken by the emir’s forces failed to secure durable allegiance. In a symbolic act reflecting Kabyle political culture, some tribes reportedly escorted Abd el-Kader out of their territory under laʿnāya (ritual protection), signaling respect for his person while unequivocally rejecting submission.

Islam and autonomy: a crucial distinction

Importantly, Kabyle resistance to Abd el-Kader did not constitute opposition to Islam itself. Kabyles were, and remain, overwhelmingly Muslim. Their resistance was directed instead at the centralization of religious authority and the fusion of jihad with state-building. For Kabyle communities, Abd el-Kader’s emirate represented not liberation, but the replacement of distant Ottoman influence with a new form of external domination—this time framed in Arab-Islamic political terms.

Historical consequences and legacy

The failure of Abd el-Kader to incorporate Kabylia into his emirate had lasting consequences. Isolated from unified resistance structures, Kabylia was later conquered by French forces between 1851 and 1857, as colonial authorities exploited internal divisions and the absence of centralized leadership.

More broadly, this episode illustrates a recurring historical pattern in Kabyle history: the prioritization of local autonomy, communal governance, and customary law over submission to centralized political or religious authority. Scholars frequently cite this tradition to explain the persistence of secular tendencies, pluralism, and skepticism toward imposed ideological systems in Kabylia’s modern political culture.

Conclusion

Kabylia’s resistance to Abd el-Kader underscores a fundamental tension between centralized Islamic state projects and decentralized Amazigh social structures. Far from being an anomaly, this resistance reflects a long-standing historical orientation toward village democracy and communal sovereignty. The legacy of this nineteenth-century confrontation continues to inform contemporary debates over identity, governance, and secularism in Kabylia and beyond.

Source

-

Eugène Daumas & Paul Fabar, La Grande Kabylie: Études historiques (1847)

-

Archive source: http://aj.garcia.free.fr/grande_kabylie/

Share this content: